Testament of Youth: a volunteer’s WWI memoir of a lost generation

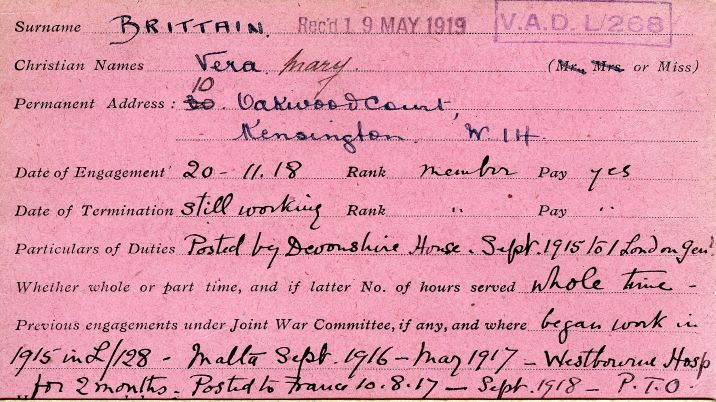

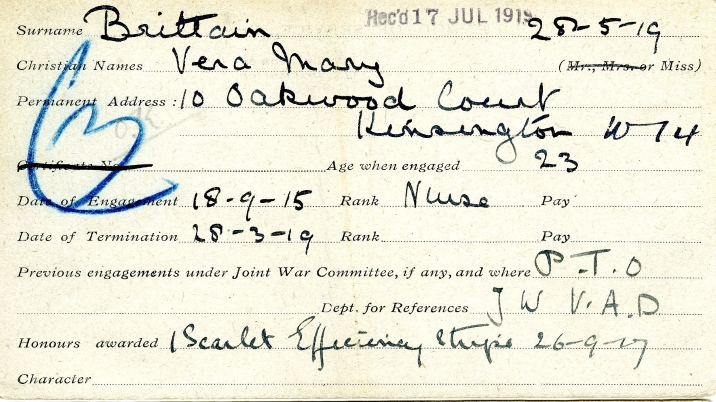

Poet and pacifist Vera Brittain was a Red Cross nurse during the First World War. In her most famous work, ‘A Testament of Youth’, she writes about her experiences as a nurse in the UK, Malta and France, where she was based at a military hospital near Étaples.

Last updated 19 April 2023

Life as a First World War volunteer (or VAD) was tough. Volunteers fulfilled a range of roles from ambulance drivers to cooks but most of the 90,000 were women who signed up as novice nurses.

Early starts, long hours and poor living conditions were just the tip of the iceberg for these raw recruits.Their on-the-job training Vera Brittain describes in her memoir, ’Testament of Youth’, as “a baptism of blood and pus”.

In it, Vera writes about her experiences as a nurse and in one extract she describes treating the victims of gas attacks: “…the hut was reserved for gassed cases, and I had once again the task of attending to the blinded eyes and scorched throats and blistered bodies which made the struggle for life such a half-hearted affair.”

Vera lost her brother, fiancé and closest friends in the war which, not surprisingly, turned her into a life-long pacifist and anti-war campaigner.

VAD vs soldier

When war broke out Vera abandoned her studies at Oxford to become a nurse out of a strong sense of duty.

With brother, Edward, fiancé Roland and two close friends Geoffrey and Victor fighting, the all-consuming life of a Red Cross VAD was, for a woman, “the next best thing” to going to the front.

It was also, for a provincial girl from a privileged background, rather exciting. With women’s options so limited before the war, the opportunity to live independently, earn a wage and maybe even work overseas was a big deal.

"After 20 years of sheltered gentility I certainly did feel that whatever the disadvantages of my present occupation, I was at least seeing life,” she writes.

Icy waters and early starts

Those disadvantages were great. From a small provincial hospital, she transferred to the 1st London General in Camberwell.

Volunteers during the World War One were housed in an uncomfortable and ill-equipped hostel. They shared small rooms divided into cubicles by curtains and washed in the dark early mornings with icy water from a basin.

Vera rose at 5.45am to be at work for 7am. Once there, the VADs received a hard time from the established civilian and military professional nurses, who were suspicious of these young amateurs, and worried about them competing for their jobs after the war.

Despite this adversity there’s no doubt Vera, a strong feminist who would later become a writer and peace campaigner, got a massive self-esteem boost from volunteering as a VAD. But her experience also formed her as a humanitarian.

Immunity from pity

Though her first sight of a gangrenous leg wound, “slimy and green and scarlet, with the bone laid bare” made her feel sick and faint, it was the “general atmosphere of inhumanness” that bothered her more.

In those early days Vera thought that the balanced efficiency of the experienced nurses demonstrated an “immunity from pity”.

“I would rather suffer ever so much in my work than become indifferent to pain,” she reflects, “I don’t mind anything really so long as I don’t lose my personality.”

The other advantage of keeping so busy was the distraction from the torment of worrying about loved ones. For Vera, loving Roland was the other major thing keeping her personality, optimism and humanity intact.

The amazing thing about the memoir is how modern Vera seems. The way she writes about the optimism of youth, thrill of work and the excitement of young love, could be the experiences of any woman in her early twenties. But as the story progresses and, one by one, the men she loves are killed, she sounds so much older than her years.

She paints such a vivid picture of the ominous atmosphere of dread following orders to clear out recovering patients on the eve of a big battle.

“Hour after hour, as the convalescents departed, we added to the long rows of waiting beds, so sinister in their white, expectant emptiness."

Fear in Titanic proportions

But even in her darkest moments, her incredible powers of storytelling give us such a vivid insight into her experiences.

Heartbroken after Roland’s death, she applies to go overseas and is sent to Malta with Red Cross, travelling on a repurposed ocean liner – the Britannic – which, it is unnervingly revealed, was built as the sister ship to the Titanic!

She and her friend are given a luxury cabin in the bowels of the ship, the location of which, considering the high risk of being torpedoed, produces a “terror at night, never spoken of”.

Intestines and impartiality

The final chapter of her VAD career is in France. After the deaths of her fiancé and two dear friends, she wants to be as close to her brother, Edward, as she can.

She is put onto the German ward, where, with complete impartiality, she and her fellow nurses forego leave and work round the clock caring for the German prisoners of war.

Finally, the distinctions between military nurses and Red Cross VADs disappear as they work together as equals.

In a hospital made of tents in the middle of winter, Vera encounters the harshest conditions yet and the most badly injured men – fresh from combat.

“At least a third were dying; their daily dressings were not a mere matter of changing huge wads of stained gauze and wool, but of stopping haemorrhages, replacing intestines and draining and re-inserting innumerable rubber tubes.”

Queen Mary inspecting Red Cross and St John VADs serving in St John hospital at Etaples, France.

Women in wartime

And then, as the war draws to a bloody climax, which will soon claim the life of her only brother, duty calls and she’s ordered home to nurse her ailing mother. This prompts one of her most interesting reflections on women in wartime.

“What exhausts women in wartime is not the strenuous and unfamiliar tasks that fall upon them, nor even the hourly dread of death for husbands or lovers or brothers or sons; it is the incessant conflict between personal and national claims which wears out their energy and breaks their spirit.”

More stories from World War I

Potato peelers, sock knitters and moss collectors

Meet the amazing volunteers who kept the Red Cross going during the First World War.

The heroic women of WW1: a nurse's diary

Peggy Arnold was a WW1 nurse serving on the frontline. Here we celebrate her bravery, and the bravery of volunteers like her.

Letters from a First World War nurse

These letters from our archive show the challenges of nursing during difficult times, as well as some of the lighter moments.