Marie Curie, the Red Cross, invisible light and WWI

Marie Curie's story is extraordinary - a discovery that changed the face of medicine, two Nobel Prizes, and service on a WWI battlefield. All in one lifetime.

Who is Marie Curie?

In October 1914, Marie Curie and her daughter, Irène were driving a rickety van near a First World War battlefield in France.

The two women were surrounded by the military – soldiers, officers, medics and the wounded. But they were meant to be there. Just two months after the war started, Marie had convinced the French government to set up the country's first military radiology centres. She was soon named director of the Red Cross Radiology Service in France.

Their van was the world's first specially fitted mobile x-ray unit, and marked the first time X-rays were taken for medical use outside of a hospital.

Many of us know her name, but how much do we know about why is Marie Curie so famous? And how did that fame allow her to make such an important contribution to medical care in World War One?

Marie Curie was inspired by the search for 'invisible light'

By the time she developed the X-ray vans, Marie Curie was already the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, then the first person to win two Nobel Prizes. She was the first woman in France to earn a Ph.D. and then the first woman professor at the Sorbonne University.

Originally from Poland, Marie was born in Warsaw in 1867. It was there that she started her studies, before moving to Paris, France age 24 where she earned her degree. There she fell in love with French physicist Pierre Curie, when they worked together at his physics lab in Paris.

When they married in 1895, X-rays had just been invented in Germany. The ‘x’ in X-ray stood for ‘invisible light’, an unknown force at the time. The Curies, together with another French scientist called Henri Becquerel, started to explore what this invisible light could be.

Using specialist equipment Pierre developed, Marie discovered that some substances gave off invisible rays that could not be changed by an outside force, such as heat or other chemicals. She realised that these rays must be coming from the substance’s own atoms.

Marie Curie called the force behind these rays, ‘radioactivity’.

What did Marie Curie discover?

Marie Curie went on to test all the elements known at that time for radioactivity. After that, she tested dozens of other things, from metals to salts. Pitchblende, a mining waste product, turned out to be highly radioactive.

To find the mysterious radioactive ingredient in Pitchblende, the Curies separated its different substances. They then measured the radiation to trace tiny amounts of unknown, radioactive materials.

By the summer of 1899, the Curies had isolated a new element and Marie named it ‘polonium’ after her home country. By December of that year, they had found another new element, ‘radium’, named after the Latin word for ray. Polonium and radium were added to Marie Curie's discoveries, paving the way for modern physics, which is responsible for many technical developments that we still use today.

The Curies then decided to find a sample of this new element. After four years of hard work, seven tons of pitchblende, 400 tons of water, and 40 tons of corrosive chemicals, they managed to extract one-tenth of 1 gram of radium chloride in 1902.

At night, Marie and Pierre watched their new element glow in the dark. “The glowing tubes looked like faint, fairy lights,” she said.

One of our joys was to go into our workroom at night; we then perceived on all sides the feebly luminous silhouettes of the bottles or capsules containing our products. It was really a lovely sight and one always new to us." Marie Curie, Pierre Curie with Autobiographical Notes

More firsts and a tragedy

In June 1903, Marie Curie’s research led her to become the first woman in France to get a Ph.D. In December of that year, the couple and Henri Becquerel were awarded a Nobel Prize in physics for their work in radioactivity.

But tragically, in April 1906, Pierre was hit by a horse-drawn cart and killed. Despite overwhelming grief, Marie continued her work on radioactivity and took over her husband’s professorship. This made her the first woman to teach at the Sorbonne.

In 1911, Marie Curie won a second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry, for her discovery of radium and polonium, and for furthering the understanding of radioactivity. She thus became the first person to win two Nobel Prizes.

The Curie's daughter, Irène Joliot-Curie, followed in her mother's footsteps. As a young woman, Irène worked with her mother running radiology units during the First World War and became her assistant at the Radium Institute. Irène Joliot-Curie is most remembered for discovering the first-ever artificially created radioactive atoms, which made way for countless medical advances and had a momentous impact in the fight against cancer.

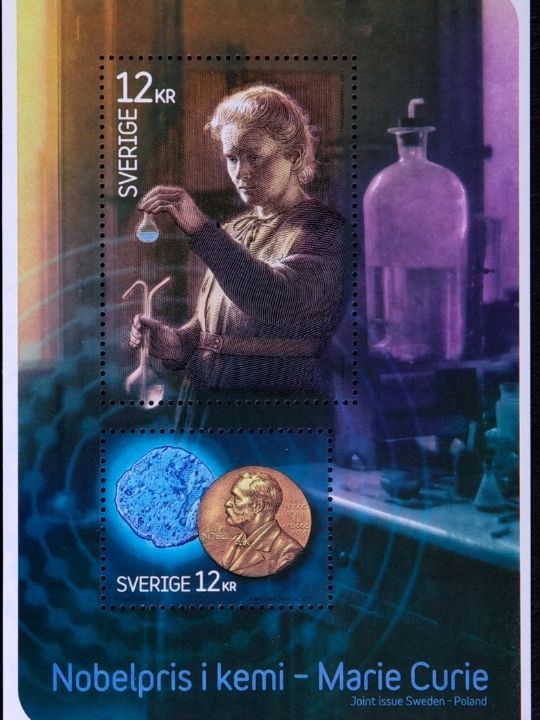

Nobel prize winner Marie Curie is honoured on a commemorative stamp from Sweden. The stamp bears a medallion of Alfred Nobel.

Serving her adopted country

Dedicated to helping France's war effort, she quickly became a war hero for her work and even volunteered to melt down her two gold Nobel Prize medals to pay for the service, but this offer was refused.

“I am resolved to put all my strength at the service of my adopted country, since I cannot do anything for my unfortunate native country now”. Marie Curie, in a letter

Your relatives may have served on the same battlefields

Over 90,000 people volunteered for the British Red Cross during the First World War, some of them treating the wounded in France. They may have come across the Curies and their mobile X-ray vans.

You can check if any of your relatives may have served on the same battlefields as Marie and Irène Curie through our WWI volunteer online database.

Marie Curie died aged 66 in 1934, of aplastic anaemia a condition caused by years of exposure during her work. The technology she and Irène developed continues to save lives on battlefields and in civilian life. Today, the International Committee of the Red Cross still cares for the health of thousands of people injured in conflicts around the world.

The Marie Curie charity carries on her legacy

The Marie Curie charity was named after the Marie Curie hospital, which was founded in Hampstead in 1930 and treated all female cancer patients. The hospital used radiology research methods pioneered by Marie, so she gave them permission to use her name.

After the hospital was destroyed during the Second World War, a committee was set up to rebuild it and separate it from the new NHS. This committee formed the beginning of the Marie Curie Memorial Foundation, which later became the Marie Curie charity we know today.

The Marie Curie charity remains the UK's largest charitable funder of palliative and end of life care research. They provide care and support for people living with terminal illnesses, as well as fighting for better support for people at the end of their lives.